Hatchets, hoes and mirrors: Deed shows how colonists bought Stamford

Stamford Advocate - July 22, 2020 Updated: July 23, 2020

By Angela Carella

From left, Alice Knapp, President of Ferguson Library and Lyda Ruijter, Stamford Town Clerk, look at the original deed of the city on July 17, 2020 at the Government Center in Stamford, Connecticut. The deed and other records from that time period are being sent for restoration and preservation by Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, Massachusetts.

From left, Alice Knapp, President of Ferguson Library and Lyda Ruijter, Stamford Town Clerk, look at the original deed of the city on July 17, 2020 at the Government Center in Stamford, Connecticut. The deed and other records from that time period are being sent for restoration and preservation by Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, Massachusetts. Photo: Matthew Brown / Hearst Connecticut Media

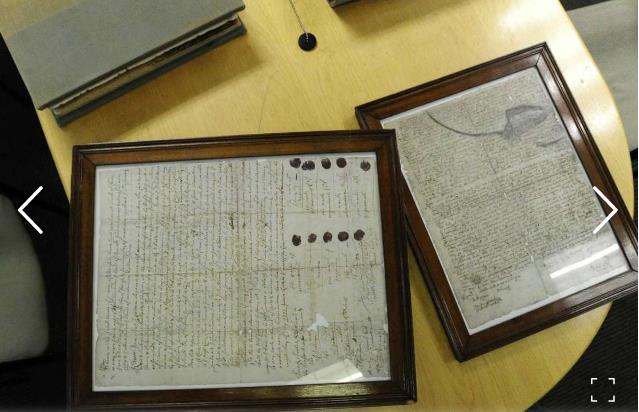

The original deed for Stamford, July 17, 2020 at the Government Center in Stamford, Connecticut.Photo: Matthew Brown / Hearst Connecticut Media

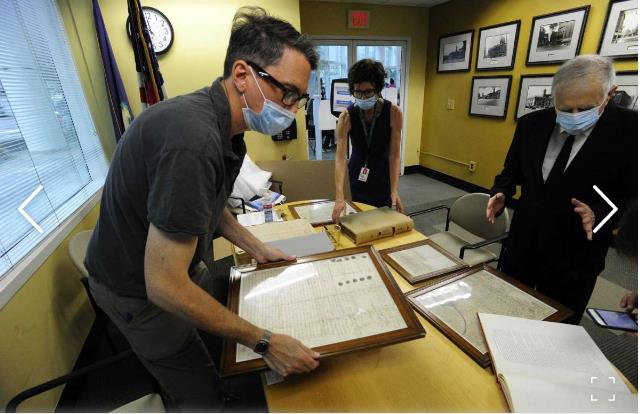

Jonathan Goodrich, a registrar for Northeast Document Conservation Center, Town Clerk Lyda Ruijter and bibliographer Ron Marcus look at the original deed of the city on July 17, 2020 at the Government Center in Stamford, Connecticut. The deed and other records from that time period are being sent for restoration and preservation by Northeast Photo: Matthew Brown / Hearst Connecticut Media

Jonathan Goodrich, a registrar for Northeast Document Conservation Center, carefully packs up the original deed of Stamford on July 17, 2020. Goodrich arrived to collect the deed, along with some other records from that time period, that will be restored and preserved by his company located in Andover, Massachusetts.Photo: Matthew Brown / Hearst Connecticut Media

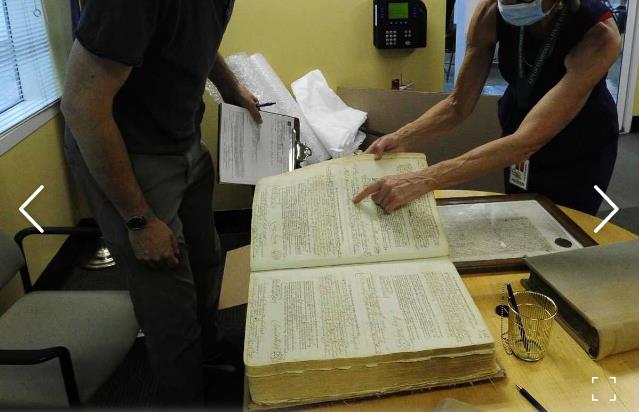

Jonathan Goodrich, a registrar for Northeast Document Conservation Center, Town Jonathan Goodrich, a registrar for Northeast Document Conservation Center and Town Clerk Lyda Ruijter look at original records of Stamford. Goodrich arrived to collect the deed, along with some other records from that time period, that will be restored and preserved by his company located in Andover, Massachusetts.Photo: Matthew Brown / Hearst Connecticut Media

STAMFORD - It may be the most lopsided real estate deal in city history.

On July 1, 1640, members of the New Haven Colony “bought” what is now Stamford, Darien, western New Canaan, and Pound Ridge and Bedford in New York from two chiefs from the Native American Siwanoy tribe.

The price was 12 coats, 12 hoes, 12 hatchets, 12 “glasses” — likely small mirrors, a coveted item back then — 12 knives, two kettles and four “fathom of white wampum” — six-foot strands of shell beads.

The deal that gave birth to Stamford was recorded in a four-page deed, handwritten on paper made of rags, that has survived time, fire and neglect.

Now the official in charge of public records, Town & City Clerk Lyda Ruijter, is seeking to have conservationists treat the 380-year-old deed so it lasts for another century or two.

Ruijter said that, for the 2 ˝ years she’s been town clerk, she didn’t know the original deed existed. That’s because it wasn’t in her office.

It was in someone else’s office.

Facilities Manager Dan DiBlasio had spotted the deed, each page separately framed, in a cabinet that was being removed from the lobby of the Stamford Government Center to make way for an electronic wall board that posts transit information.

“I didn’t know what it was. I just saw a sign in the cabinet that said, ‘These are Stamford’s earliest and most historic documents,’” DiBlasio said. “I thought, ‘Whoa. If that’s true, then this belongs somewhere else.’ I put it in my office just to make sure nothing happened to it.”

After Ruijter became clerk in 2017, she began an effort to save historic city records stored in an abandoned police precinct building on Haig Avenue.

DiBlasio recently told her about the 1640 deed in his office.

Ruijter contacted an Andover, Mass., company, Northeast Document Conservation Center, to get an estimate of what it will cost to preserve the deed and other records she found from the 1600s. Jonathan Goodrich, a registrar with the nonprofit center, met Ruijter in her office Friday to collect the documents.

“The conservators will take these to the lab, unframe them and get a close look at the condition of the paper,” Goodrich said. “They’ll test the inks for water solubility because documents can be cleaned in a water bath to leach out pollutants, reduce acidity and help them stay supple for a longer time.”

Such documents survive because they were printed on paper partly made from rags, Goodrich said. Pure wood pulp paper couldn’t cut it.

“We’ve treated quite a few old town deeds,” he said.

The Stamford deed has the wax seal of the Colony of Connecticut, which is not unusual, Goodrich said. But he doesn’t recall seeing seals such as 10 others that are fixed to the Stamford deed.

They appear to be the thumbprints of native American chiefs and their aides from the Siwanoy tribe.

“They did that when they signed a deed in the 1600s,” said Ron Marcus, a researcher with the Stamford History Center.

The deed was signed, with a name or a mark, by Capt. Nathaniel Turner, head of the New Haven Colony, and the Siwanoy chiefs.

Wascussee was sagamore, or chief, of Shippan, which was pretty much Shippan Point as it is today. Wascussee’s mark was an oval with a line through the middle. Ponus was sagamore of Toquam, which was all the land from Shippan north to Pound Ridge. Ponus’s mark looks like a W with an extra arm.

Ponus kept some land along the Rippowam River for planting, but, according to the deed, “the above-said Indians Ponus and Onox (Ponus’s son) with all other Indians that be concerned in it have surrendered all the said land to the Town of Stamford as their proper right forever.”

That may not have been the chiefs’ understanding, Marcus said.

The settlers, following the European way of conveying land, drew up a wordy deed explaining how they walked the land and carved the letters “ST,” presumably for Stamford, into certain oak trees to mark the boundaries.

Native Americans “didn’t buy or sell land in that way,” Marcus said. “They went to war over good hunting territory or good places to plant corn, but they did not accumulate land.”

Still, the city prospered, though the land got carved up over time — Stamford now is half its original size.

The deed, however, very nearly died.

At one point it was stored in a town hall at Atlantic, Bank and Main streets downtown. But in 1904 the town hall burned down.

“The town clerk got there as the fire started and called for people to help him get the records out. There was only one copy of everything,” Marcus said. “They passed the books to each other, bucket-brigade style, and saved them all except the very early tax records. They saved the deed, too.”

A new building was constructed on the site — it’s known now as Old Town Hall, the city’s preeminent historic building - and the deed was stored there. But not well, Marcus said.

“In the 1960s, then-Town Clerk Lou Clapes found it in a little room in the bell tower of Old Town Hall,” Marcus said. “It was covered in heavy dust. It was under glass, but some of the glass had cracked.”

Marcus is the one who 55 years ago put the pages of the deed in the frames that DiBlasio spotted in the cabinet and moved into his office.

Preserving history is a precarious business, Marcus said.

“We’re lucky to have that document,” he said. “Just plain lucky.”

acarella@stamfordadvocate.com; 203-964-2296.